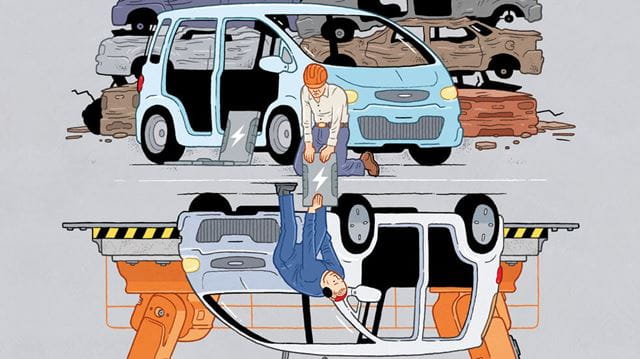

In part four of our ‘Future of motoring’ series we look at how electric vehicles will change the way we recycle cars and their parts

As fossil fuels are gradually replaced by electricity, will we be capable of recycling enough to keep discarded vehicles out of the ground while leaving precious minerals and metals in it?

The number of cars on our roads is one thing, but what about where they go when their time is up? Every year, end-of-life vehicles account for around seven to eight million tonnes of waste in the EU – and this is bolstered by scrappage schemes such as the one offered by Ford, which scrapped 25,500 cars in the UK throughout 2017 and 2018 as a result of its ongoing deal.

Not only that, but with the age of the electric car fast approaching, figuring out the best ways to reuse or recycle spent lithium-ion batteries is an ever-increasingly critical topic.

Before we get stuck into the complexities of electric-vehicle recycling, let’s start with the older cars. Those that are left, anyway. An awful lot of them were lost forever when the government ran a scrappage scheme back in 2009 and 2010 – a move that was intended to encourage dwindling new-car sales and simultaneously remove older, more polluting vehicles from our roads.

It sounds like a win-win, apart from one thing – the fact that you could get £2,000 off a new car if you handed in your old one meant that many buyers condemned perfectly healthy cars that could otherwise have remained in use. The scheme was well-intentioned and saw some 390,000 motorists obtain a new car for a good price, but it also meant that swathes of old yet serviceable cars were sent to the scrapyard.

And, sadly, even the good ones couldn’t be saved, as any car taken in under the government-backed scheme had to be scrapped. So the Porsche 928s, Honda Integra Type Rs, Toyota Supras and more that were handed over had no hope of rescue.

Essentially, as long as the ‘money for your old car’ message continues to shift new vehicles, and with the London mayor now also offering cash to drivers who swap in an old car that isn’t exempt from the capital’s new Ultra Low Emissions Zone, the scheme doesn’t look like coming to an end.

On a less depressing note, both vintage and modern cars are eminently recyclable. Since 2016, the UK has bettered EU targets set out for vehicle recycling, managing to recycle some 90% of the materials contained in scrap cars. Indeed, it’s thought that up to 25% of the steel contained in new cars comes from recycled vehicles.

More of our expert views on the future of motoring

How fuelling stations will change with the EV revolution

… what will the cars look like inside

And will we continue to own our cars or just borrow them?

Recharging your batteries

Electric cars are trickier – or, more specifically, their batteries are. The Global Battery Alliance estimates that there will be 11 million tonnes of spent lithium-ion batteries to deal with globally by 2030. However, the problem is not insurmountable, and while there are significant improvements to be made, the recycling and re-use of electric-vehicle batteries is already big business.

Most lithium-ion batteries are recycled using a process of hydro- or pyro-metallurgy that sees the batteries broken down into parts and the metals melted down for re-use.

Of course, there are still improvements to be made. Dr Gavin Harper, a research fellow involved with The Faraday Institution’s ReLiB project, explains: “We are currently designing systems that will enable us to ascertain the condition of recovered car batteries. This will allow us to ‘triage’ batteries into different streams for re-use and recycling, and also characterise their chemistries, which will lead to more efficient recycling.”

The ultimate aim for the ReLiB project is to improve battery recovery, recycling and re-use to an extent that the precious metals from used batteries will provide 99% of materials needed for new battery production, reducing demand for freshly mined metals to virtually zero.

Those involved with the project are not alone in wanting to achieve this cyclical life cycle for batteries. Tesla CTO JB Straubel said in 2018 that Tesla is “developing more processes on how to improve this recycling process... ultimately, what we want is a closed loop that re-uses the same, recycled materials”.

There are many and varied reasons for wanting to do this, all of them good. The key materials needed for battery production include lithium and cobalt. Both have environmentally woeful mining processes involved, and there are atrocious human-rights violations involved in the sourcing of cobalt in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Plus, of course, it’s very expensive to source and buy. So, the battery and car-manufacturing industries are heavily invested in improving the recycling process for fiscal, political, moral and environmental reasons alike. But recycling isn’t the only way to maximise our use of car batteries.

Used or refurbished batteries have great potential as energy storage systems. Nissan already offers home energy storage units that utilise second-hand Nissan Leaf batteries, and also uses the same batteries in large-scale installations including the Johan Cruijff Arena in Amsterdam.

Putting the brakes on

There are, however, arguments against using car batteries for stationary energy storage. Batteries for transport applications must provide lots of power in a small, lightweight cell, which is what these valuable metals are best served to do. As Dr Harper says: “If we think about domestic applications, the energy density isn’t so critical. Some feel we should focus precious resources on the most demanding applications, including electric vehicles.” Mercedes-Benz would agree.

In 2017, the German manufacturer launched a home energy storage system using batteries from its range of EVs, but the product was axed a year later, with the company claiming that “it’s not necessary to have a car battery at home. They don’t move, they don’t freeze... it’s overdesigned.”

The reality is that there will be multiple solutions relying primarily on methods of recycling and re-use, and actually designing new batteries and cars with the recycling process in mind will also be a crucial part of making such complex recycling easier.

The good news is that the recycling technology is there and effective already, as are the incentives to improve and upscale that technology in the coming years. Even potential future tech, such as solid-state batteries – which would require chemical-separation techniques also being developed currently – is accounted for in extensive research and design being carried out.

Put simply, the materials used in the manufacture of cars and batteries are too valuable for them to go to waste and environmental doom in landfill. So, while the loss of some of our old cars may be a nagging disappointment to those of us who have a passion for vehicles – not to mention a questionable environmental move – the silver lining is that the global automotive community is already stepping up to the task of keeping our cars, new and old, out of the ground.

Crunching the numbers

- 30: The number of Toyota Supras given over for scrappage in 2009. Three BMW M3s and 14 Audi Quattros were also handed in that year. They would all be MOT’d to be eligible.

- 1991: The year that Sony introduced the first commercialised rechargeable lithium-ion battery, which helped to improve the battery performance on the company’s video cameras. 90% How much of the global lithium-ion battery recycling is expected to be taken up by large- capacity vehicle or stationary power storage systems by 2030.

- 392,277: How many cars were scrapped in the 2009/2010 government-backed scrappage scheme before the allocated £400m of taxpayers’ money ran out.

- 13 million: The estimated number of cars that could be made with the steel reclaimed from all the cars recycled in the USA and Canada each year.

- 63: The number of used Nissan Leaf battery packs that help to make up the largest battery power storage facility in Europe, at the Johan Cruijff Arena in Amsterdam.

- 158%: The jump in sales of pure electric car in July 2019 compared with July 2018, with 12,000 pure electric car sales sold in the first half of the year according to the SMMT.

- 60%: The percentage of the average electric car battery that is made up of the cell itself. The rest is made up of the casing, wiring, adhesive, tubes and busbars.

- 11 million: The number of metric tonnes of lithium-ion batteries that are expected to require recycling in 2030, as forecast by the Global Battery Alliance.