From nursing to ventilators, antiseptics to ibuprofen, meet the British pioneers who've helped to save millions of lives across the generations

The coronavirus pandemic has turned a brilliant spotlight on the skill and dedication of the NHS, as well as the resourcefulness and community spirit of millions of ordinary citizens. But the whole sophisticated infrastructure of modern healthcare has been built up over centuries, as past scientists, doctors and entrepreneurs have solved one medical challenge after another.

So if you’re looking for a silver lining to the coronavirus cloud, consider these pioneering Brits, whose innovations paved the way for today’s hi-tech healthcare system. With British scientists now in a global race to create a vaccine for Covid-19, perhaps more names will soon be added to this illustrious roster.

Epidemiology – John Snow (1813-1858)

Few of us knew much about epidemiology until 2020, when it became the most talked-about scientific discipline in the world. The study of epidemics goes all the way back to the ancient Greeks, but in its modern form it owes much to the Victorian physician John Snow. In Snow’s day, the epidemic was cholera, which – over a series of outbreaks – killed over 20,000 people in the UK, and millions worldwide. Snow was the Yorkshire-born doctor who traced the source of an 1854 Soho outbreak to one specific water pump, proving that the mysterious ailment was a water-borne infection, and paving the way for a vaccine. He went on to co-found the Epidemiological Society of London, one of the first organisations to study pandemics.

Nursing – Florence Nightingale (1820-1910)

Every child learns about the ‘Lady with the Lamp’, who brought comfort to the wounded soldiers of the Crimean War. But Florence Nightingale’s compassion was matched by a ferocious intellect, and her evidence-based approach to patient care laid the foundation of modern nursing. She introduced far higher standards of hospital hygiene, used statistics and infographics to model the effects of different treatments, and introduced proper training for generations of nurses. Founded by her in 1860, the Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery remains the UK’s highest-ranked training centre for nurses, and one of the best in the world.

Antiseptics – Joseph Lister (1827-1912)

As you reach for the antiseptic hand gel, give thanks to Joseph Lister. Prior to this pioneering surgeon’s discoveries in 1860s Glasgow, infections were thought to travel through miasma or ‘bad air’. Opening hospital windows was as far as sterilisation went. But, building on the work of the French chemist Louis Pasteur, Lister used weak carbolic acid to sterilise his surgical instruments, operating theatre and patient wounds, with stunning results. His work launched the whole field of antiseptics, and his name lives on – rather prosaically – in one of them: Listerine mouthwash.

Social care – Octavia Hill (1838-1912)

Two important aspects of the current pandemic – voluntary social care and open spaces – were long ago championed by this feisty Victorian reformer. Growing up in a London characterised by desperate poverty, Hill pioneered better housing for the poor, and laid the foundations for modern social work with a network of volunteer visitors to struggling households. Her belief in “the life-enhancing virtues of pure earth, clean air and blue sky” led to the preservation of many of London’s open spaces, and to the creation of a great British institution: the National Trust.

Handwashing – William Hesketh Lever (1851-1925)

The ‘Lever’ in today’s multinational conglomerate Unilever was William Hesketh Lever, who got into the soap business back in 1885. Warrington-based Lever Brothers developed and sold the first truly mass-market soap, Sunlight. Coinciding with greater public awareness of how germs carry, the brand was vastly successful. Production hit 450 tons a week (that’s nearly 500 VW Beetles-worth of soap), and it spawned a new model village for workers on the Wirral, Port Sunlight. Sunlight soap remained a UK market leader through the early years of the 20th century, and the brand continues to thrive overseas, including in Belgium and Sri Lanka.

Pharmacies – Jesse (1850-1931) and Florence (1863-1952) Boot

Photo: theislandwiki.org

That mainstay of the British high street, Boots the Chemist, owes its existence to an entrepreneurial couple, Jesse and Florence Boot. Jesse inherited his father’s Nottingham herbalist store, and with Florence transformed it into the 'Chemists to the Nation'. The company pioneered the shift from traditional remedies to patent medicines, delivering the reliable products and trained advice we take for granted today. True progressives, Boots employed the first analytical chemist, opened a 24-hour pharmacy in the 1920s, and introduced a raft of benefits for employees.

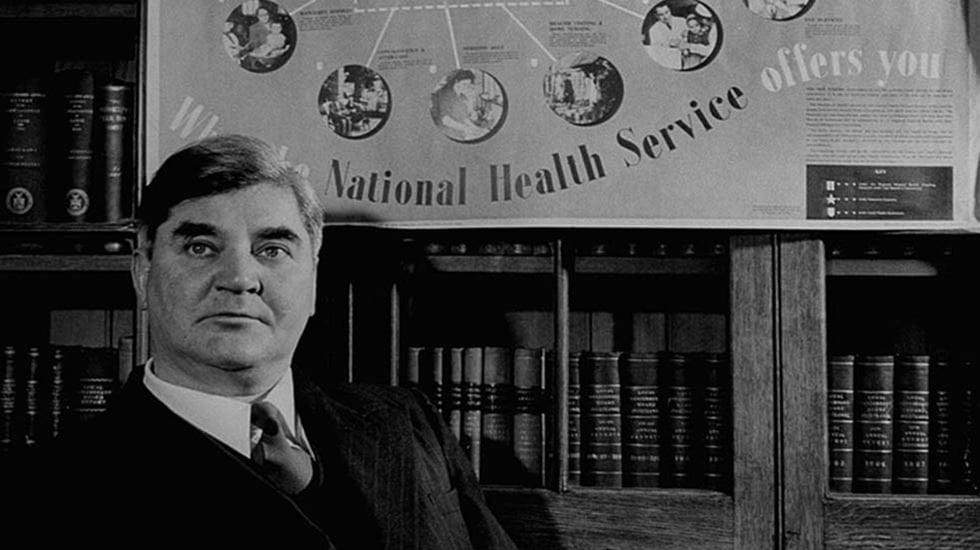

The NHS – Aneurin Bevan (1897-1960)

It’s been called Britain’s greatest invention, but the NHS might never have existed without the grit and political skill of one man: Aneurin ‘Nye’ Bevan. The 1940s Labour Minister for Health said he saw himself less a politician than a “projectile discharged from the Welsh Valleys”, and he brought that intense energy to the complex business of reshaping Britain’s shattered post-War medical infrastructure. Bevan shepherded the NHS Bill through Parliament, conceived the regional structure of the service, and did much to personally establish the ‘ground rules’ that endure today. Launched on 5 July 1948, the NHS became a living response to Bevan’s passionate belief that “no society can legitimately call itself civilised if a sick person is denied medical aid because of lack of means”.

The ventilator – Roger Manley (1930-1991)

Photo: liftl.com

In the early months of the coronavirus outbreak, a key concern was the lack of ventilators to treat patients in intensive care. Numerous teams including a Formula One consortium raced to support the NHS with these machines, and interest was revived in a now-basic but once cutting-edge ventilator design: the 1960s Manley Ventilator. Although ventilators have a long history, they were either huge, cumbersome pieces of apparatus or electrically powered – which carried a risk of explosion in operating theatres. Roger Manley was a Westminster Hospital doctor who designed an elegant, gas-powered ventilator in his garage in 1961. Manufactured by Blease Medical, it revolutionised anaesthetic practice and became standard equipment throughout Europe for decades, only recently giving way to today’s computerised devices.

Gene sequencing – Frederick Sanger (1918-2013)

The race for a coronavirus vaccine relies on our knowledge of the virus’s genetic sequence, which was first published by Chinese scientists in January 2020. But how do you sequence a genome? The answer was first provided by British biochemist Frederick Sanger. Working at a Medical Research Council lab in Cambridge over several decades, Sanger successfully sequenced both DNA and RNA (the two types of genetic material), and invented the Sanger Method of sequencing that is still in use today. For his pains, he was awarded not one but two Nobel Prizes in Chemistry – a unique achievement.

Ibuprofen – Stewart Adams (1923-2019)

Photo: Wikimedia Commons / Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4

If you’re treating the coronavirus at home, NHS advice suggests taking paracetamol or ibuprofen to help bring down a high temperature. Paracetamol’s history goes back to 1880s America, but for ibuprofen we have to thank Northamptonshire research chemist Stewart Adams. Adams spent the majority of his career working at Boots, where he led the team researching anti-inflammatories to treat arthritis. After many years of research dead-ends, he made the breakthrough in 1961 with ibuprofen, today one of the world’s most important painkillers. He knew it worked, he later told the BBC, because it helped him alleviate a hangover.

Photos: Getty Images unless otherwise stated