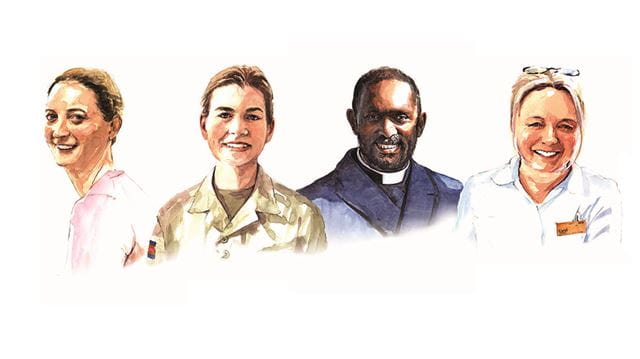

When you think of the public sector, images of nurses, firefighters and police officers probably spring to mind, but the range of roles that go unseen is far more varied than you could ever have imagined. In the build-up to Public Service Day on 23 June, we talk to four individuals with truly fascinating – and somewhat unexpected – day jobs.

Rev. Brent van der Linde RN

Chaplain, Royal Navy

I serve on board HMS Defender, offering comfort, council and confidence to people of all faiths and beliefs. Put simply, I help to look after the sailors and am a friend to them all – no matter who they are. It’s a privilege to share part of their life journey with them: by being a listening ear, cheering them on to do better, or giving advice to deal with a difficult situation.

There’s no such thing as a typical day, but I always walk around the entire ship: this can take the whole morning, because I have conversations with everyone I meet. I call in on the Captain, brief the Command Team about the morale on board, and have lunch with the Junior Rates. This is always fun – we have a laugh and I tell them my terrible jokes.

I am based in Portsmouth, but in the last year I’ve been away from home for around 300 days. Living on a warship, you build strong relationships very quickly. The wonderful thing about our role is that it doesn’t have a rank, so we can move easily across all personnel. I can ask the same questions of the young Able Seaman and the Captain. In turn, they can have a conversation with me about any concerns or challenges they face, outside the chain of command.

I am a Christian Minister, but we have many different religions represented on board. I help people to celebrate and engage with their beliefs: by putting them in contact with their own faith leaders, for example, or by ensuring they have the right resources for prayer.

I’ve been in the Royal Navy for just over two years, but I never really set out to do this job. I come from a youth outreach and peace-building background in South Africa and Northern Ireland. But one day I was invited to see what Royal Navy Chaplains do, and I fell in love with the people and organisation. The personnel are among the bravest and dedicated people I have ever met, and it’s an inspiration to serve them.

Camilla Moore

Receiver of Wreck, Maritime & Coastguard Agency

There are countless shipwrecks and sunken cargo in the waters around the UK, and you wouldn’t believe some of the things that wash up on our beaches. Anybody who finds and retrieves a significant item, either while underwater or on the coast, is legally required to report it to the Receiver of Wreck – and that’s me. I’m the only one in the UK.

Technically, ‘wreck’ consists of anything that has come off a vessel in distress – so we deal with everything from old rusty nails to really valuable cargos of silver. We track down the rightful owner of the item, and make them aware that it has been found. I also liaise with the finder, or ‘salvor’, and award them compensation for their efforts.

My background is marine archaeology, specialising in wreck pollution, so I have a very strong working knowledge of salvage law. Identifying the owner can be like finding a needle in a haystack: we sift through public notices, insurance documentation, shipwreck records – anything that might tell us where the item has come from. Once notified, the owner has a year to claim it; after that, it becomes property of the Crown.

Sometimes items will turn up on our doorstep, anonymously. We’ve had a couple of ships’ bells do that: one recently from an American wreck (that we’ve just returned), and most famously the SS Mendi’s, which was returned to South Africa in 2018.

I love the variety of the role – I've always been interested in shipwrecks, and some of the historical records are absolutely fascinating. And every case is so different: we’ve had people report everything from hot tubs and beer tanks, to a ‘ghost’ ship that washed up with nobody on board. Alongside that, commercial salvers actively seek out wrecks in British and international waters, so we occasionally deal with large amounts of bullion – real treasure! These old valuable finds are usually sold to museums, with the salvor receiving a cut of the proceeds.

After storms, things can get really hectic. Bad weather washes up all kinds of things, so you’re braced for a very busy few days in the office. I’m always wondering what will turn up next – and often it’s a complete surprise.

Major Emma Jude, MBE

Senior Veterinary Officer, British Army

You can’t do this job if you’re not a dog lover – and the same goes for their handlers, who also work with the dogs every day. But we don’t only love them for sentimental reasons: they are an essential part of the Armed Forces. For detection of explosives, there is no better weapon than a dog. And for non-lethal escalation of force – at riots, for example, or while patrolling a base – they are essential.

The Royal Army Veterinary Corps (RAVC) has two main units, and I’m part of the 1st Military Working Dog Regiment which is based in Rutland. Our dogs are deployed to support soldiers on exercises and operations all over the world. I am the senior vet within the regiment, so it’s my job to ensure the dogs get the best level of care.

I worked as a civilian vet before joining the army ten years ago. The RAVC looks after all of the animals in the service, including the Household Cavalry’s horses and some rather cute mascots: we have goats for the Royal Welsh regiment, a ram for the Mercian Regiment, and Shetland ponies for the Royal Regiment of Scotland. One of my previous roles was to provide them with veterinary assistance, so I got to know them all pretty well.

Different dog breeds have different capabilities, so they work according to their strengths. Detection dogs – such as labradors and spaniels – are trained to seek out explosives and weapons. Protection dogs – like German shepherds and Belgian malinois – play a more security-focused role.

There are roughly 900 service dogs across the entire Armed Forces. If a dog is injured, whether at home or while deployed, we will do everything we can for it. Even if it can’t return to service, we will rehome it – and that's really important for the morale of our soldiers. Often, a dog will be rehomed with its handler: their bond really is unbreakable.

Last year, I was recognised on the New Year’s Honours list for my part in an explosives training project. I was flabbergasted, but we really were just doing our jobs. The dogs mean the world to us, so we do everything we can to keep them happy and healthy.

Carol Mabey

Head of Orthotics and Prosthetics - Community Division, Isle of Wight NHS Trust

Even after 30 years working in prosthetics, it still gives me goosebumps to see the impact of our team – to witness how it can transform people’s lives. Our patients have either had an amputation because of a disease, such as diabetes, or were born with limbs that hadn’t developed fully. As prosthetists, we are trying to replace what they’ve lost – or give them what they have never had.

First we assess their needs: What is their lifestyle like? Do they require a special type of limb? Then we capture the shape of their residual limb, wrapping it in plaster to make a mould – which we then use to create what we call a ‘socket’. This sits between their residual limb and the artificial limb, and each one is utterly bespoke. When we have the fitting, we work with the patient to ensure the socket is perfect for them: modifying, trimming, making it as comfortable as possible.

Each prosthetics centre in the country has its own workshop, where technicians craft the sockets from various materials. We usually use hand-made moulds – though in some cases 3D scanning is preferred. The combination of skills required in prosthetics is very unique: you need to be a scientist, a medic, an engineer – and also have a certain artistic flair.

I did my degree in chemistry, then worked in a lab for a year – but I re-trained because I wanted to do something more meaningful. At the moment there is a real shortage of prosthetists, because until recently there were just two universities that did specialist training. But soon there will be an additional apprenticeship system so people can train on the job, and the government has announced a £5,000 annual grant for trainees. It will open up this remarkably rewarding career to so many people.

I’ve been managing this service for 15 years, but I am still very hands-on in my role. I do clinical work, whilst also managing the department and staff – but the plaster room, where we make the moulds, is still a big part of my day. You’re working directly with patients, on a mission to make their lives better – and wow, I don’t think I’ll ever tire of that buzz.

For more information on starting a career with the NHS, click here.